The re-introduction of a “youth development” rule was one of the biggest developments before the current Liga MX season. This rule states that for each club players born in 1997 or after must receive a total of 765 minutes across a single tournament (e.g. Apertura), with a maximum of 270 minutes per match counting towards the total. Failure to fulfill this requirement results in a three point deduction.

Many praised this rule, but there were plenty of valid concerns about its potential effectiveness. Tigres coach Ricardo “Tuca” Ferretti raised an excellent point when saying that it could result in players, that aren’t ready, getting a few games one season, before being replaced when they no longer count as a “young player” under the Liga MX guidelines. This could lead to a long-term negative impact on youth development, as some players, like Oribe Peralta or Luis Reyes, develop later in their careers.

Another critique of the rule is that it misses the point, that a lack of top quality canteras in Mexico is the real issue. After all, teams that are producing young talents (Pachuca, Santos, América, Atlas, Chivas) give their youngsters game time, because they’re good enough to have a positive influence on the pitch. Using a stick approach, and forcing teams to give “young players” a certain number of minutes is arguably unlikely to incentivise clubs that aren’t currently producing many youngsters to make the decision to invest heavily in improving their academy.

We are only five games into the season, and it’s extremely early to think about assessing the impact of this new rule. However, an interesting pattern has emerged with the positions of young players that have received minutes this season.

For this article, we will only focus on outfield players. Almost every Liga MX team has played a 4-2-3-1 or 4-4-2 formation with their outfield players this season, which offers the opportunity to simply split the pitch up into five pairs. Two centre-backs, two full-backs, two defensive/central midfielders, two wingers and two strikers/a striker and an attacking midfielder.

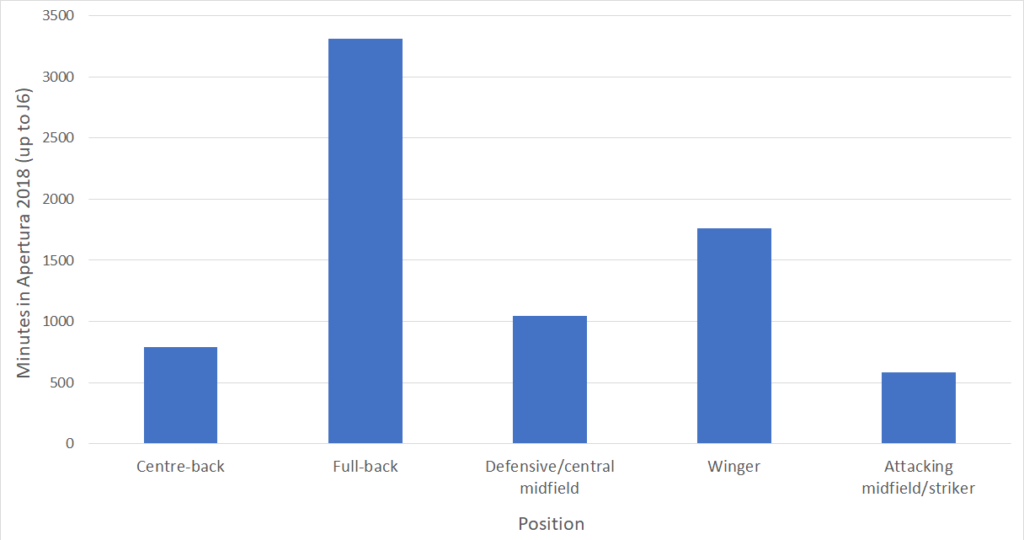

The total number of minutes for Mexicans born in or after 1997 this Apertura, so far, is 7,482. If these minutes were evenly split between the five position pairs on the pitch, we would see 1,496.4 minutes per pair.

The actual split, shown below, is very different.

Minutes per position for Mexicans born in 1997 or afterwards in the 2018 Apertura

Full-backs dominate the chart, with the total of 3,309 minutes more than double the figure if minutes were evenly distributed across the pitch. Wingers contribute the second highest number of minutes, with 1,759. Minutes for centre-backs (787) and attacking midfielders/strikers (582) are well below 1,000.

The trend is increasingly interesting when breaking-down the pitch into central and wide areas. Combined, minutes for full-backs and wingers makes up over two-thirds (67.7%) of total game time for Mexicans born in or after 1997.

There are a huge number of potential factors in creating this distribution of minutes. Perhaps the most pertinent comes down to the question of trust.

Every position on the football pitch is crucial, but arguably, players out wide aren’t quite as important as central players. This is especially significant when it comes to making errors, with errors in the centre of the pitch usually more dangerous than errors in wide areas. If youngsters aren’t well trusted, and are viewed as players that can potentially make errors, placing them in wide areas would seem a safer option for a coach than using them centrally.

A coach that’s forced to give a young players a certain amount of minutes, but doesn’t particularly trust or feel that the youngster(s) is ready, may see playing someone in a wide area as the best or safest option. Not particularly helpful if the aim of the “development” rule is to aid the creation of a Mexico squad that’s strong across the pitch. Tigres’ Jair Díaz, who’s preferred position is reportedly centre-back, has been used at left-back in recent games, and he could be an example of this phenomena taking place.

Even without the necessity to play youngsters, before the introduction of the rule, this trend can arguably be observed. Possible centre-backs Carlos Vargas and Jesús Angulo added their names to the ever growing list of potential national team left-backs last season, whilst centre-back options appear limited.

The bias towards defensive players, i.e. full-backs getting more minutes than wingers, links back to a study of mine in 2017. This study split Liga MX players into mostly defensive and most attacking players, and looked at how many of each were Mexican, and how many were foreign. Three jornadas in the 2017 Clausura were studied, and a bias towards Mexican defenders and foreign attackers was shown. For example, in jornada 14, foreign players made up 36.8% of defenders, but 64.8% of attackers.

Jesús Angulo emerged spectacularly as Santos won the 2018 Clausura, but like the other full-backs Santos have produced in recent years, there’s questions over whether he can add attacking output to his consistent defensive displays

There’s always the possibility that the trends found are cyclical, and will change in time, but it could also be that Mexico’s academies are currently more effective at producing full-backs, and wingers, than players in other positions. This could certainly be said for Santos Laguna, who have brought through José Abella, Jorge Sánchez, Gerardo Arteaga, Gael Sandoval and Angulo in recent years.

If true, this would be concerning, especially when considering the differences between wide and central players. Players in wide areas spend much of the match having only around 50% of the pitch available to pass to, and without the ball wide players have the benefit of the sideline as an additional defender. It takes increased awareness, vision and tactical knowledge to be able to play with options, in and out of possession, all around you. The lack of central youngsters coming through could suggest that Mexican academies are struggling to create players with the requisite awareness.

It’s important to remember that we don’t have data for minutes per position before the introduction of the new “youth development” rule, and therefore it’s impossible to say whether the distribution has become more or less even across the pitch. However, the current situation, if it is to continue, isn’t particularly desirable, and doesn’t appear conducive to Mexico building an all-round strong squad in future years. Therefore, whilst we can only theorise whether or not the “youth development” has worsened the distribution, it can definitely be said that, so far, it hasn’t proven an effective solution.

More quality academies, both at Liga MX level and below, and a clear method of transition from youth football to the intensity and pressure of Liga MX, is required for Mexico to push on to the next level of national team quality. The overly-simplistic “youth development” rule doesn’t address either of these necessities. It is likely that the rule will result in increased minutes for young Mexicans in comparison to last season, which many media outlets will see as a source of praise for Liga MX, but the distribution of minutes across the pitch will greatly limit the positive impact of this increase.

Comments